Why did I write a book about an obscure TV series few remember?

Why I wrote an unofficial guide to 'The Man in Room 17'.

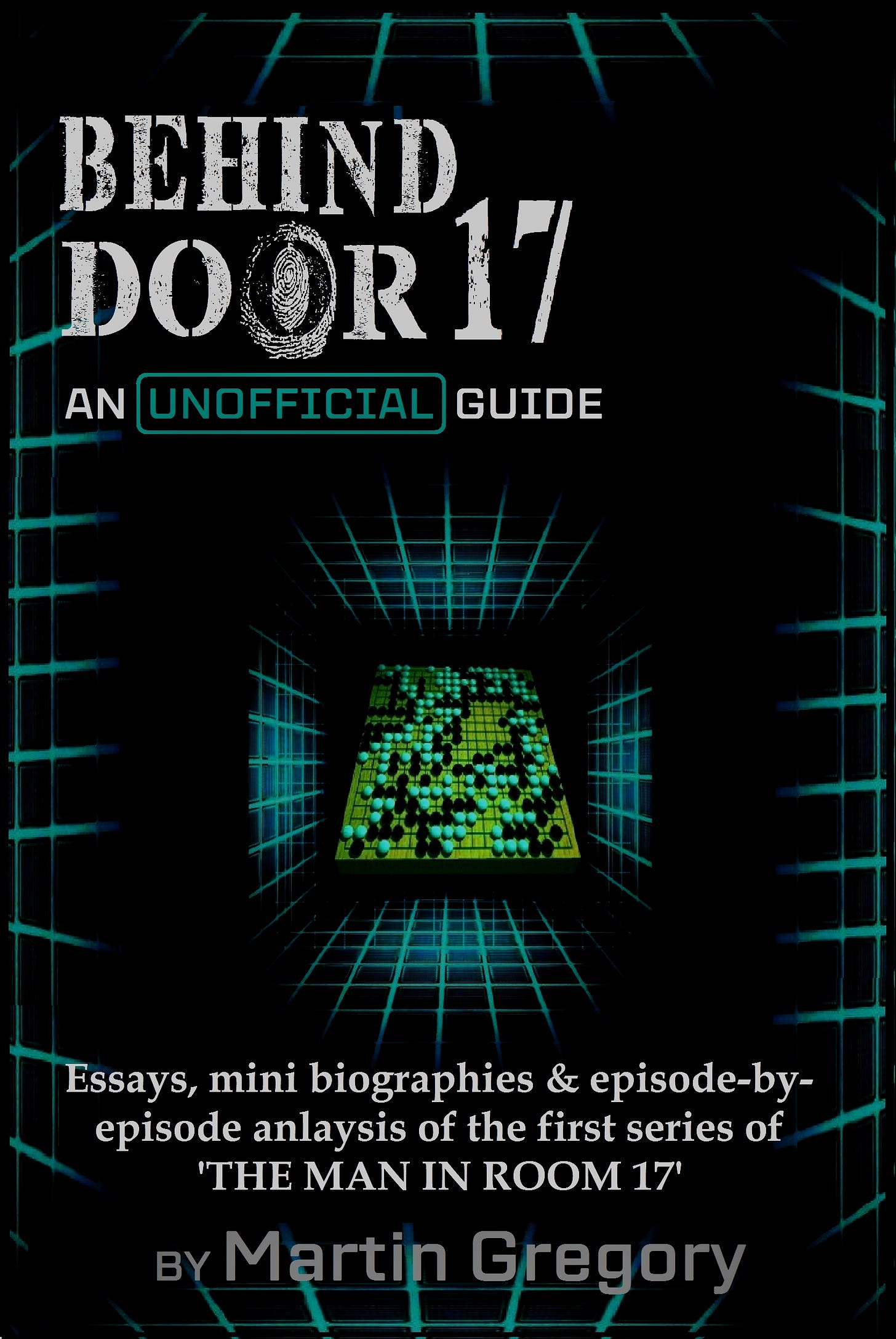

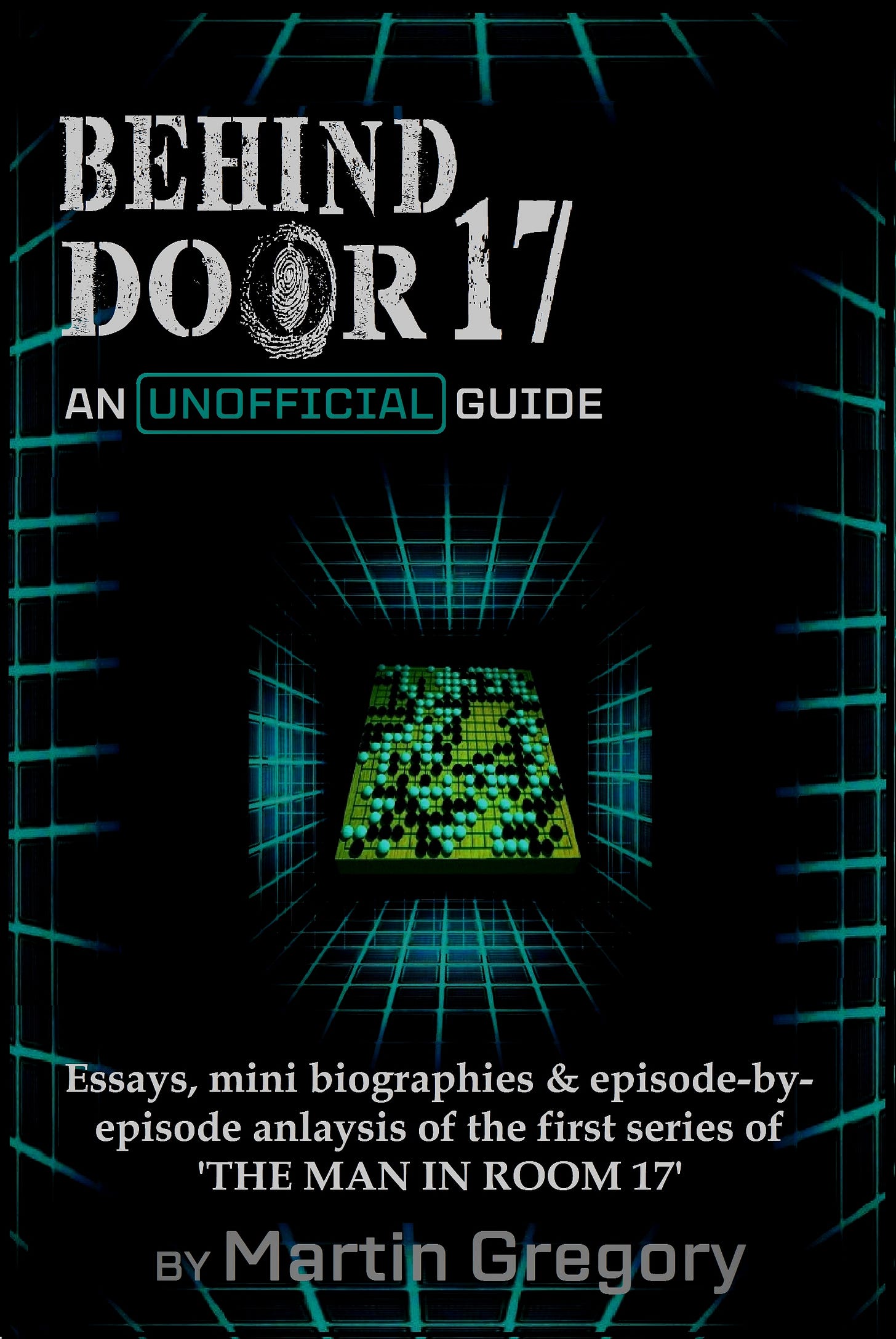

Regular subscribers to will know that I was writing a book – a guide to an old and rather forgotten piece of television called ‘The Man in Room 17’. The book is now complete and available to buy (HERE) but the question remains; If the subject is so old and forgotten, why write a book about it?

If I revealed the reasons, not only will I have divulged a secretly held theory about generational shifts in viewing habits, the slow but definitely building trend for ‘deep-dive, I would probably have made more sense than I just did. Let it suffice to say, I have reasons.

So, what’s ‘The Man in Room 17’ about? On the surface, it’s about two criminologists solving mysteries and uncovering crime from inside a secret room somewhere in Whitehall (London). Nestled in the grey areas between the police and the Home Office, between intelligence services and the Crown, the purpose of Room 17 is to use whatever means at their disposal to solve problems.

Edwin Oldenshaw and Ian Dimmock are the criminologists, the puppeteers that never leave their room, instead relying on a series of different agents to be on the scene and report developments. The existence of Room 17 is a closely guarded secret and is just one branch of the British intelligence counteroffensive against ‘the enemies of democracy and freedom’. Such things were very important to survivors of a war against fascism (the second world war), and dramas set in this world of espionage became very popular in the 1960s.

What also became popular in the mid 1960s was a quirky aesthetic applied to television programmes. It started with ‘The Avengers’, in which the characters Steed and Mrs. Peel dealt with ever more outlandish villains in ever-more off-beat stories. The ‘Batman’ series starring Adam West and Burt Ward perhaps exemplified the nadir of this approach.

At the opposite end of the scale we have the serious, albeit slightly tongue in cheek, spy drama like ‘The Saint’, ‘James Bond’ and ‘Man in a Suitcase’. ‘The Man in Room 17’ sits somewhere between the two genres. At times deeply whimsical, other times it’s positively philosophical.

‘The Man in Room 17’ was the brainchild of a young writer called Robin Chapman – a writer who, after penning ‘Room 17 and two sequels – caused an uproar with the levels of violence in a series called Big Breadwinner Hog. The network cancelled the series about the leaders of two rival gangs before the last episode aired, causing a great deal of embarrassment for all concerned. The characters Chapman invented for his first show are far removed from the gangs depicted in ‘Hog’. Occupying the secret room of the title is Edwin Oldenshaw, an Oxbridge type with an enquiring mind, a questioning nature and quite the raconteur. Ian Dimmock is younger than his colleague. Though he has a wealth of experience of his own, is frequently deferential to his colleague’s experience, power of recall and ability to focus his mind.

The programme makers at Granada Television at this time were an innovative, experimental bunch. Basically, they wanted to test the feasibility of making a series where all the scenes featuring the main characters would take place on the same set, and recorded separately from the ‘action’ scenes by a director working solely on the ‘room scenes’. A novel idea, in a way pre-figuring a film shoot made up of multiple units. A practice established in the world of motion pictures, but not on television. It was new and experimental and the really fascinating thing is, it actually works.

In my book ‘Behind Door 17’, I take a very detailed look at the stories that make up the first thirteen episodes of the first series, examining the characters and taking a moment to reflect on things we learn about Oldenshaw and Dimmock as the series progresses. Sometimes the nature of the production, the ‘received pronunciation’ prevailing in the acting profession at the time (sounding posh, basically) and the occasional technical shortcomings often provide an existential barrier to enjoying vintage programmes from the black and white era. Outdated technology and the director’s tendency to cut away from violence also pose a barrier to some. I cover both in sections of the book.

Certain things lots of viewers of archive television prefer to look away from, such as cultural stereotypes get a mention in my book too, as do the things that were happening in the real world at the time each episode was being written and filmed. The episodes themselves are often very topical, filtering recent real-life events of the mid 1960s into the drama and allowing the characters to react to situations, policies and practices, much as viewers at home were doing at the time. By viewing these episodes in context, we can make interesting comparisons and parallels to the modern world. '

To viewers born this century, I think there’s a level of curiosity about the world and how it functioned in the pre-internet age / analogue era. ‘Behind Door 17’ lifts the lid on these aspects of vintage telly, hopefully serving to make these classic shows of yore more accessible.

It is a series with a gently, almost imperceptible unfolding narrative. Unusually for the time, the series does not ‘reset’ at the beginning of each new installment. It takes four or five episodes for this to become apparent, however. The casualness with which conversations and happenings are referred back to is really unarming. I’m so used to shows from this era ignoring character development, preferring to snap everything back to where it was the previous week. It’s interesting to see a young writer challenging the norms in this way, and having the confidence to do it.

Robin Chapman loved his creations, Oldenshaw and Dimmock. He liked to prod them and make them jump, putting them through emotional and intellectual assault courses. Often presenting them with situations and associates purely to see how they react. Almost as if somebody, distinctly un-academic, was having the time of his life playing with these intelligent would-be autocrats, showing us that intelligence and a beguiling mind can be as much a curse as anything else.

The book contains essays on various aspects, such as the pronounced ‘deep state’ subtext of the series, how a secret network of autonomous departments is part and parcel of the world they inhabit. I also explore the show’s origins, explaining the creation and rationale behind this experimental television program. This, along with a critical essay, forms the triumvirate of essays as central to the book as the episode-by-episode analysis.

In many ways, the book is not just a guide to one television programme, but to others made at a similar point in time. A window into the world now long gone and an era of programme making consigned to history but written with a celebratory tone, because these shows are not to be hidden. Forgotten, sure. I can live with forgotten because there’s so much quality material out there and freely available – far more than that available to contemporary 1960s audiences, but not hidden. Nor derided for the outmoded ideals or values. But celebrated as tiny miracles of celluloid. When you think about the technical constraints they were up against – the limits of technology – what we have to look back on are monumental endeavors of the like we have become so very accustomed. The past is a foreign country, so to transport one’s mind back through the decades, to tune into this show and in tandem tune oneself into the minds of 1960s viewers is interesting, illuminating and fun. At least it is in my hands.

Order Behind Door 17 - An Unofficial Guide to ‘The Man in Room 17’ HERE

The deep state exists!

Somewhere in the depths of Whitehall two shady puppeteers pull strings, manipulate events and, via their ‘tentacles’ in the outside world, defy their superiors to affect the international order - all from the confines of their cosy office.

Starring Richard Vernon (A Hard Day’s Night, Goldfinger, The Hiitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) as the former code breaker and Cambridge intellectual Edwin Oldenshaw and Michael Aldridge (Last of the Summer Wine, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Charters and Caldicott) as his intellectually equal but frequently playful colleague. Written by Robin Chapman (Big Breadwinner Hog, Boon, Tales of the Unexpected), ‘The Man in Room 17’ is a fine example of the ingenuity and ideology prevalent in those working for production juggernaut Granada Television in the mid 1960’s.

Includes:

Thirteen chapters providing episode-by-episode analysis including transmission information, details on the many guest stars to appear in the series and a look at the outdated technology used by Oldenshaw and Dimmock, the mythology surrounding Room 17 and cast and crew information. Plus, notes, observations and more.

A critical essay on the first series of ‘The Man in Room 17’

The Beginning - an in depth look at the genesis of ‘The Man in Room 17’; Where the idea originated, how it was developed and how the series was received

The Deep State is Real - an essay exploring the 'subtext' of the series

Mini biographies of all major contributors to series one, both in front of and behind the camera

Separate character analysis for the major characters, Oldenshaw and Dimmock.

The ‘instant’ guide

Uncover the secrets and go behind door 17 with this essential companion to the intelligent, witty and occasionally irreverent first series of ‘The Man in Room 17’

Order Behind Door 17 - An Unofficial Guide to ‘The Man in Room 17’ here

Make your friends love you forever and share my Awesome Audio Reviews.

Awesome Audio Reviews is the home of audio appreciation. Narrated audiobooks, dramatisation, comedy, children’s, classics and oddities. This is where we show the love. Shout loud the appreciation for audiobooks of all types and times. A place to release your inner nerd and feel the love for all things audio.

I’m Martin Gregory and I’ve been listening to audiobooks since I was five years old. Throughout school, I was the quiet kid browsing the audiobooks in the local and school library. I may have fallen off the wagon a few times over the years, but basically been listening to audiobooks all my life. A life in audios, you could say.

My tastes are wide ranging. I enjoy a good mystery story, crime dramas and the great detectives of literature. I do like a bit of a giggle and the output of BBC Radio is an especially rich vein to mine. And I’m a sci-fi buff. Hard SF, humorous or thought-provoking. Children’s stories get plenty of attention from me too, getting into the classics and contemporary tales for the audiobook fanatics of the future. And then there’s contemporary offerings seething with originality. There’s room for all types and all tastes.

Read the reviews, find out where to find the audios you want to hear and tell your audiobook-loving friends. There’ll be the undeniably obscure, the classics, the famous ones and reviews for those that enjoy a ‘deep dive’. If you’re determined to go down the joyous rabbit hole of awesome audios, this is definitely the best place to start.

Martin Gregory Writes

The deets, backstories and secrets behind my writing projects. Keep updated with my latest releases, plus occasional thought-pieces and freebies.

Subscribe for free

copyright Martin Gregory 2025